The Poems Game

A multiplayer online Balderdash-style game for writing poetry.

Play the game here.

Instructions

- Create a room and invite others by sharing the link.

- Choose a poem or input your own.

- Read the first n-1 stanzas of the poem (the last stanza is automatically hidden for you).

- Spend 10-15 minutes writing your own versions of the last stanza. It’s useful to have a time cap here especially if you have some perfectionists in your group. You can send multiple submissions if you want. Once everyone has submitted their version (remember to pay attention to formatting and indentation), one person hits the “All submission are in” button.

- All ending submissions will be displayed in a random order (everyone gets the same order). Read them and talk about them.

- Hit the “reveal” button to see the real ending.

E.g.

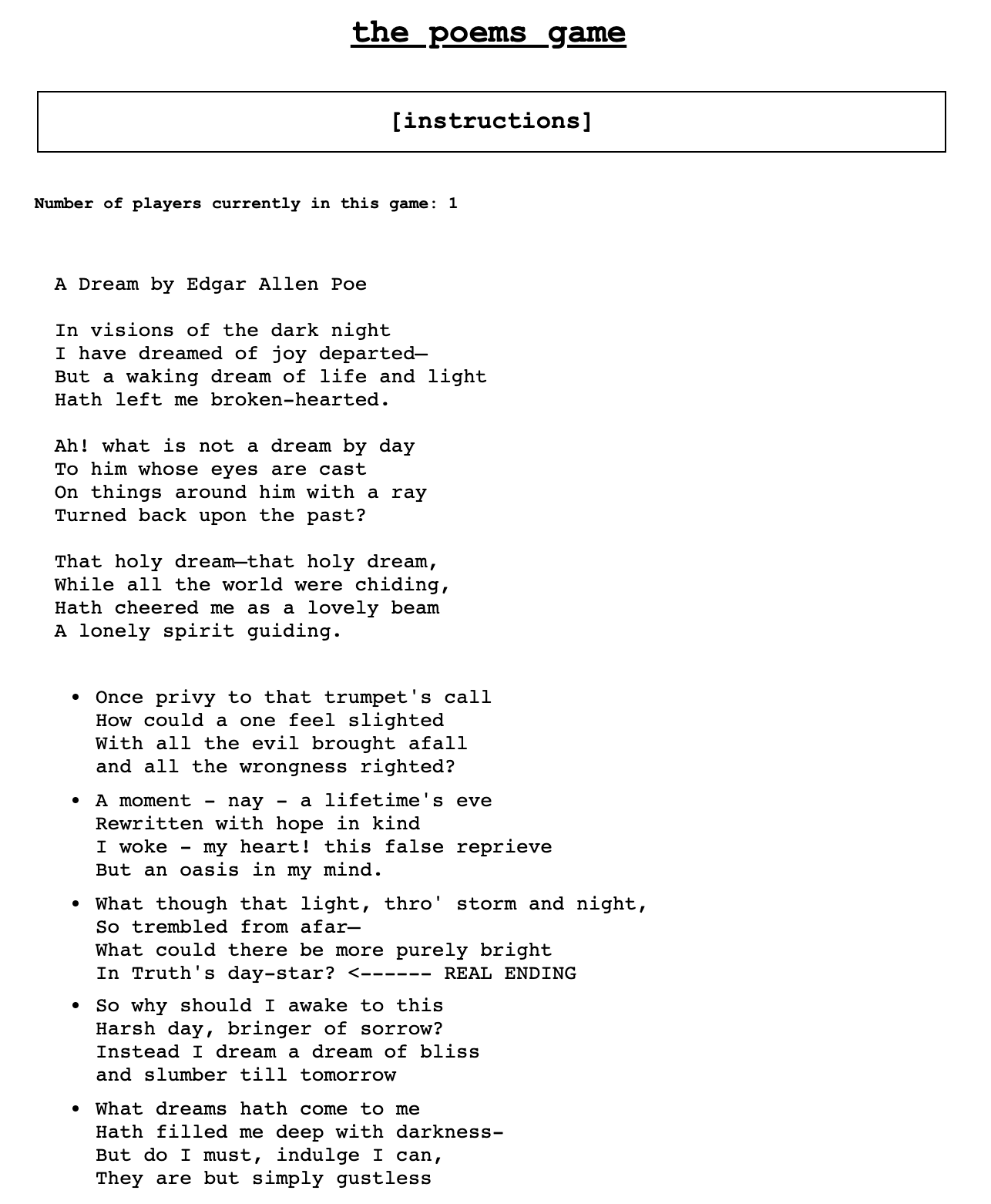

An example of a poem with several submitted endings.

About

I used to play this game with my roommates, but entirely by hand.

We would find a poem without reading the last stanza and write our own endings on slips of paper, trying our best to match handwriting by writing in all caps. Then one of us would write the ending down as well, which meant they could not participate in the guessing portion. It turned out that it’s just as fun to write an ending and get to see how other people wrote their endings as it is to actually guess.

During the guessing round, if you wanted to, you could usually narrow down which ending was real based on which two slips of paper had the same precise handwriting, as whoever wrote the real ending would have also written their own ending.

In a few years of playing this game, we became skilled at making fake endings. Some simple tricks include using old timey words like “privy, nay, hath,” making a strange comparison that one would never think would be poetic, as a form of countersignalling, and coining terms (what even is a “day-star”).

We also got pretty good at reading and grokking poetry. The creation of new work in the correct style necessitates a strong understanding of the style itself. Often I would read a poem thinking I basically understood it, but only when asked to write my own ending did I truly read the poem carefully enough to understand everything that was happening in it, and all the directions it might go.

This same principle turned out to be true for larger works. For example, in the development of a musical set in Shanghai in 1920-40, I learned more about Chinese history than I did in 12-16 years of schooling that apparently never stuck. The reason it stuck this time is that I was trying to picture the era clearly enough to write a story in it.